The number one question I get asked when installing a new phone system has to be “How do I transfer a call?” Seems that most people who have been using phones most of their adult lives are mystified by the little button that allows them to send a call somewhere else. Especially when I put the complexity of a Voice over IP (VoIP) phone system in their hands.

The majority of people that have been using Private Branch Exchange (PBX) phone systems for the past few decades should be familiar with basic unsupervised transfer. You may also hear this referred to as a blind transfer or a cold transfer. In this implementation, the party initiating the transfer presses the transfer button, dials the number that the call needs to go to, and is then disconnected from the call. The original caller is sent to the new target and when the target answers, they get an earful of whatever the original caller wishes to tell them. They call this blind (or cold) because the other party has no idea it’s coming. Some people, especially executives, get kind of upset by all this messy blind stuff.

Most modern phone systems use a method of supervised transfers. These are also called consult transfers or warm transfers. These kinds of transfers start out the same. A called party presses the transfer button and dials the number of the person that needs to get the phone call. In this case, though, the called party stays on the phone until the target picks up. All the while, the original caller is hearing the dulcet tones of Streaming Winds (or whatever your music on hold happens to be). When the target picks up, you get to give them all the gory details of the phone conversation so far, out of earshot of the transferred party. Only when the person on the other end agrees to take the call do you complete the transfer by pressing the Transfer button again. It’s a warm transfer because the target gets to hear a friendly voice before the original caller gets to launch into whatever they want to talk about. It’s still possible for you to pull off a blind transfer in this setup. When the target’s phone starts ringing, you press the transfer button to complete the transfer. Now, the original caller will hear the target’s phone ringing and they get to start talking as soon as the phone picks up. In some cases, depending on how the transfer caller ID works, this can be worse than a blind transfer, because the target will see the caller ID of the original called party and think it’s someone internally wanting to talk, only to get an outside caller when they answer. It’s caused some embarrassment before, I can assure you.

For whatever reason, some people have a problem with warm transfers. Especially if they are used to blind transfers. They hang up on the original caller, thinking the transfer went through with no issues. The problem is that the call won’t complete until the transfer button is pressed twice, meaning that hanging up without pressing it twice will disconnect the caller. Then they get to call back, angry they’ve been disconnected. No amount of training in this world has been able to break people of this bad habit.

Cisco Unified Communications Manager (CUCM) doesn’t have an option for blind transfers. It’s a consult transfer system only. However, there is an option you can set that will act like a blind system and allow your users to act as they always have without disconnecting callers.

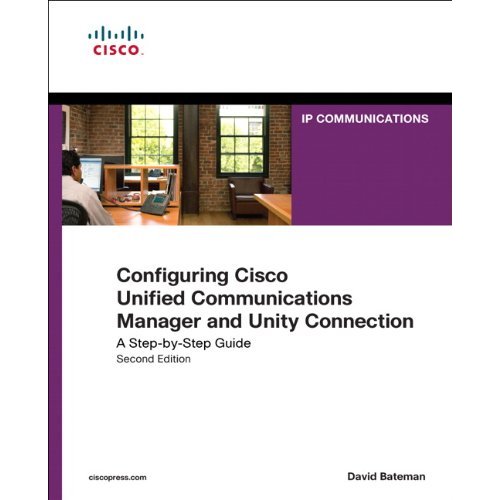

- Log into your CUCM publisher and go to the System menu.

- Choose the Service Parameter option.

- Choose the publisher server from the dropdown menu.

- Choose the Cisco CallManager Service.

- Scroll down until you find the Clusterwide Parameters (Device-Phone)

- Look for the Transfer On-Hook Enabled setting. By default, it’s set to FALSE.

- Change this setting to TRUE to allow On-hook transfers.

Here’s a picture in case you get lost:

Easy as cake. If your phones are all SCCP-based, the setting will take effect immediately. If you phones are SIP, you’re going to have to reset them to change this, so be sure to do it when you can reboot them all without affecting communications.

There you have it. Once you’ve enabled this little setting, you can still use a warm transfer, but those users that can’t or won’t transfer with the Transfer button can still pull off a transfer by hanging up without disconnecting the caller. If you can find a way to drill the concept of a warm transfer into the heads of those that just don’t seem to get it for some reason, you can make some real money. Sure, it may involve some heavy duty mind control, but in the end I think it will all be worth it.