I’m no electrician. In fact, the last time I tried to do some electrical work ended up with a minor electrocution and me not being able to taste for an hour. However, in the IT world electricity is a key to our jobs. The mightiest Nexus 7k or QFabric deployment can be brought to its knees by inadequate power. The need to understand power and the the connectors that go along with it are vital.

Fabulous secrets were revealed to me the day I pulled up the Internet and started looking up the various codes for connectors that are used in electrical work. I figured out pretty quickly that electricians had a language all their own and that I needed to learn how to speak some of it in order to get things accomplished. After all, describing a connector as “one goes like this, the other goes like that” isn’t really helpful, especially over the phone. I wanted to pass on a bit of what I learned to all of you. A note for my international readers: this is going to be focused primarily on US connectors. However, if you’d like to fly me to your country for a few days, I’ll be more than happy to bring a travel kit and research your electrical code from my hotel room. Just a thought…

Some of these connectors standardized by the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). They also hold the trademark on the term “twist lock”, so when I use it, know that it belongs to them. The others are standardized by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) under IEC 60320.

NEMA 5

The NEMA 5-series plug and receptacles are the most common found in the US today. They are three-wire circuits (hot, neutral, and ground) and are rated to carry a maximum of 125 volts, although they usually carry about 110 volts and are referred to as “110 circuits”. All of these connectors will start with a “5” and a dash, followed by the amperage of the circuit, from 15 amps to 30 amps.

5-15

By far the most common connector you’ll run into in the US. A simple 110-125v circuit rated at 15 amps. Whatever you do, don’t rip the ground plug out if you need to fit this into a NEMA 1-15 two prong outlet. I’ve seen what happens there and it isn’t pretty.

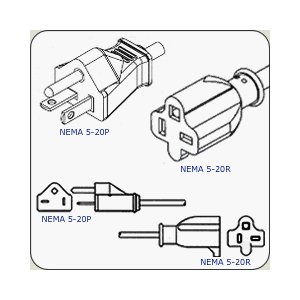

5-20

The NEMA 5-20 connector is more common as you being to start using equipment with high wattage power supplies, like Catalyst 4500 switches. I’ve always heard the 5-20 described as a “dedicated circuit” plug, but that’s not entirely accurate. It’s a 110-125v 20 amp circuit. It can easily be identified by the perpendicular blade.

L5-20

Here’s where the real fun starts. This little jewel was the source of my first head scratching moment with NEMA connectors. This plug is the same as its 5-20 cousin above, however the connectors look all wrong. This connector is designed to be inserted into the receptacle and then rotated counterclockwise to lock it in. This way, it can’t simply be pulled out by someone tripping over it or by vibrations from heavy machinery. Do take care though, as tugging on the connector too hard will cause it to rip the whole receptacle assemble out of the wall with possibly some exposed wires.

L5-30

The NEMA L5-30 is the big boy of 110-125v circuits. I found it curious that I have never really seen the non-locking version of this plug, but I’ve since been informed that the majority of devices that use 30 amp circuits prefer this connector to prevent it from being yanked out. Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPSs) use this connector frequently in order to ensure their devices are getting enough power.

NEMA 6

The NEMA 6 series connectors are the ones you use when you need to provide heavy duty power to a device. These are typically 208 volt or 240 volt circuits, but I’ve always heard them referred to as “220 circuits”. There is no neutral wire in this setup, as both non-ground wires are delivering power. These are the kind of connectors used in the home for things like air conditioners or clothes dryers. In my experience, the standard versions of these connectors are uncommon. The locking version are used far more frequently, usually do to the fact that whatever is running off of that much power probably doesn’t want to go offline due to having a power plug kicked out of the wall. These connectors all begin with a “6” followed by the amperage of the circuit, usually between 15 and 30 amps.

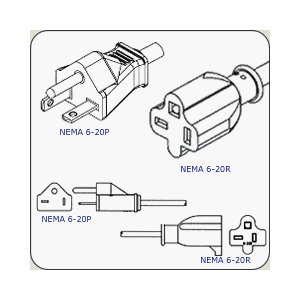

6-20

The only non-locking NEMA 6-series connector I run into on a regular basis is the 6-20. Note that while this plug/receptacle is similar to it’s 5-20 cousin, the perpendicular blade is the opposite on this connector to prevent you from plugging the wrong cord into the wrong plug and getting a nasty surprise.

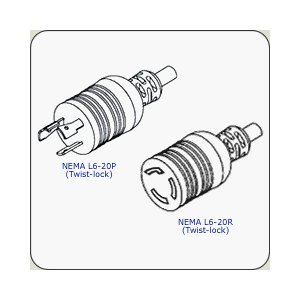

L6-20

The locking version of the NEMA 6-20. Far more common due to the ability to keep whatever this cord is powering plugged in. Odds are good that if you are using a heavy duty power supply in a device like a Catalyst 4500 or a Catalyst 6500, you’ve got this cord powering your device.

L6-30

Big devices call for big power. This 208/240v 30 amp circuit connector is going to power just about anything you can throw at it. Big UPSes or huge power supplies in a switch like the 8700 watt monster in the Catalyst 6500. You are most likely to encounter this connector in a rack-mounted PDU where it provides the power coming from the main electrical connection and then the PDU disperses the power to the devices in the rack itself.

IEC 60320

The IEC connectors are fairly common in electronics devices, however I believe that most people couldn’t pick them out of a lineup. That’s because the IEC connectors are the ends that are on the opposite side of the cord from the power plug. These ends plug into power transformers and power supplies. By making them an international standard, the equipment manufacturers need only put one kind of receptacle on their equipment and then manufacture the various country-specific cords when needed. Also, unlike the NEMA connectors above that use “P” and “R” to denote plugs and receptacles, the IEC connectors use a different number to specify the plug and receptacle, for instance the IEC C19 is the plug and the IEC C20 is the receptacle.

C7/C8

This connector is used for power transformers, laptop power supplies and small appliances, like the original Playstation. This connector is shaped like a figure 8, unless you have the polarized version when is squared off on the hot end. I’ve spent many an hour looking for one of these connectors for a forgotten device.

C13/C14

If you’ve ever worked with a computer, you know this power cord. In fact, for the majority of my career I’ve called it a “computer power cord”. This particular IEC connector run everything from desktop computer to fixed-configuration switches. I always carry two or three spare cables with me at all times just in case I need them. I’m also starting to see more and more higher wattage devices requiring two or more cords to work properly, like server power supplies or the newer power supplies for chassis switches. The C14 plug is also very common on power strip type PDUs for racks where you plug the C13 end into your server and the C14 end into the PDU. Saves a bit more space than the NEMA 5-15 connector above.

C15/C16

Odds are good you’ve seen this cable and said “Huh?”. I’ve started seeing it ship with newer fixed-configuration switches that had Power over Ethernet (PoE) power supplies. For the life of me, I couldn’t figure out the point of changing this connector. A chance comment from one of my friends about this so-called “kettle cord” made me start researching what was so special about the connector. It turns out the C13/C14 connector/cord is only rated to about 70 degrees F. The C15/C16 was specifically designed for higher temperature devices, like electric kettles and PoE switches with higher wattage power supplies, like those that drive 802.3at or PoE+ 30 watts per port. This connector will work in the C13/C14 receptacles, but not vice versa. This prevents the cord melting and causing all kinds of trouble.

C19/C20

If you’ve ever installed a Catalyst 4500 switch, you’ve seen this plug on the power supply. For a long time, I referred to it as the “chassis switch power connector” without knowing it had a real name. The C19/C20 connectors are used for devices that require a higher current than that which can be provided by the C13/C14/C15/C16 connectors. I’ve only ever seen it on chassis switches, but it can also appear in high end workstations or some kinds of UPSes.

Tom’s Take

When you stare at the long list of power options available for a switch or a server, you might find your eyes crossing at the multitude of unfamiliar acronyms you find. At best you’ll end up with an extra power cord you don’t need. At worst, you could delay a large project for many days because you ordered an L6-20 cord when you really needed a 5-20 connector. The same goes for ensuring you have the correct power connections hooked up in your server closet or data center. Electricians aren’t sure what you’re talking about when you tell them you want a “winking man” connector or “the twisty one” kind of plug. If you tell them you need an L5-20R, they’ll be able to put one in without asking another question. Network rock stars always talk about the virtues of standardization and the electrical world is no different. By knowing the standard name for the NEMA or IEC connector you need, you can be sure that you are the one that has the power.

This article is going directly to my list of references when buying Cisco’ stuff. Thanks!

You are slightly incorrect on a few things.

240V power (ie. as delivered into your house) DOES have a ground, and it can be delivered on a NEMA-L14 connector. If you measure 240V to the ground, you have a 120V circuit on each half. In the data center, the 208V circuits do not have a “ground” as you say, voltage is delivered over two phases of power and both legs are “hot”, each leg is out of phase to one another.

Also inside the data center, power strips that have IEC-C13 receptacles aren’t doing it for space reasons. It is because those are 208V feeds. Almost every piece of datacenter grade gear will auto-voltage and take 208V or 120V power, so feeding equipment off C13 outlets or 5-15 or 5-20 receptacles doesn’t matter to the gear, it’ll auto adjust to the voltage. In the end, the only diff will be the amperage will be lower (ie 0.58 of the usage of 120V) on the 208V feed. Lower amperage lets the datacenter install normal sized wiring and deliver more power, although 208V circuits take up twice the panel space than 120V circuits do.

The IEC-C19 outlet strips are also 208V fed. As you stated, the C19s can take higher amperage loads (16A @ 208V), vs the C13s which are rated lower (10A @ 208V).

Thanks for the corrections Doug. Most of my experience has been around 110/120V circuits. Always welcome to hear from someone that has more knowledge on the subject than I.

C19/C20, as I’ve seen it, is a major connector type for input line in rack PDUs with C13/C14 outputs. Also, C19/20-type seems to be a primary output for most of 1-phase UPSes ranked over 3000VA we had installed.

Oh, and a C13-C14 cable is generally called “a UPS cable” here in Russia.

A minor correction: C14 plugs are rated for 70 *celcius*, not farenheit. That’s plenty high for any type of IT equipment; you have some overzealous designer to thank for whatever you found with the kettle cord. Maybe they were trying to keep people from using grab-bin C14 cords that can’t handle the maximum rated current with a device that draws close to the max, but most equipment in that scenario has the C20 cord instead.

Great article: If I want to connect a USB 3.0 powered drive to a C14/C13 outlet strip, is the connector called a C13/C14 to 5-15 adapter? Need to order it and don’t know what to call it. Thanks.

I think the third image on the 6-20 is incorrect (the front on image of Nemea 6-20P is wrong). Looks like a 5-20P by accident.

Cheers.