Do you present to an audience? Odds are good that most of us have had to do it more than once in our life or career. Some of us do it rather often. And there’s no shortage of advice out there about how to present to an audience. A lot of it is aimed at people that are trying to speak to a general audience. Still more of it is designed as a primer on how to speak to executives, often from a sales pitch perspective. But, how do you present to the people that get stuff done? Instead of honing your skills for the C-Suite, let’s look at what it takes to present to the D-Suite.

1. No Problemo

If you’ve listened to a presentation aimed at execs any time recently, such as on Shark Tank or Dragon’s Den, you know all about The Problem. It’s a required part of every introduction. You need to present a huge problem that needs to be solved. You need to discuss why this problem is so important. Once you’ve got every head nodding, that’s when you jump in with your solution. You highlight why you are the only person that can do this. It’s a home run, right?

Except when it isn’t. Executives love to hear about problems. Because, often, that’s what they see. They don’t hear about technical details. They just see challenges. Or, if they don’t, then they are totally unaware of this particular issue. And problems tend to have lots of nuts and bolts. And the more you’re forced to summarize them the less impact they have:

Now, what happens when you try this approach with the Do-ers? Do they nod their heads? Or do they look bored because it’s a problem they’ve already seen a hundred times? Odds are good if you’re telling me that WANs are complicated or software is hard to write or the cloud is expensive I’m already going to know this. Instead of spending a quarter of your presentation painting the Perfect Problem Picture, just acknowledge there is a problem and get to your solution.

Hi, we’re Widgets Incorporated. We make widgets that fold spacetime. Why? Are you familiar with the massive distance between places? Well, our widget makes travel instantaneous.

With this approach, you tell me what you do and make sure that I know about the problem already. If I don’t, I can stop you and tell you I’m not familiar with it. Cue the exposition. Otherwise, you can get to the real benefits.

2. Why Should I Care?

Execs love to hear about Return on Investment (ROI). When will I make my investment back? How much time will this save me? Why will this pay off down the road? C-Suite presentations are heavy on the monetary aspects of things because that’s how execs think. Every problem is a resource problem. It costs something to make a thing happen. And if that resource is something other than money, it can quickly be quoted in those terms for reference (see also: man hours).

But what about the D-Suite? They don’t care about costs. Managers worry about blowing budgets. People that do the work care about time. They care about complexity. I once told a manager that the motivation to hit my budgeted time for a project was minimal at best. When they finished gasping at my frankness, I hit them with the uppercut: My only motivation for getting a project done quickly was going home. I didn’t care if it took me a day or a week. If I got the installation done and never had to come back I was happy.

Do-ers don’t want to hear about your 12% year-over-year return. They don’t want to hear about recurring investment paying off as people jump on board. Instead, they want to hear about how much time you’re going to save them. How you’re going to end repetitive tasks. Give them control of their lives back. And how you’re going to reduce the complexity of dealing with modern IT. That’s how you get the D-Suite to care.

3. Any Questions? No? Good!

Let me state the obvious here: if no one is asking questions about your topic, you’re not getting through to them. Take any course on active listening and they’ll tell you flat out that you need to rephrase. You need to reference what you’ve heard. Because if you’re just listening passively, you’re not going to get it.

Execs ask pointed questions. If they’re short, they are probably trying to get it. If they’re long winded, they probably stopped caring three slides ago. So most conventional wisdom says you need to leave a little time for questions at the end. And you need to have the answers at your fingertips. You need to anticipate everything that might get asked but not put it into your presentation for fear of boring people to tears.

But what about the Do-ers? You better be ready to get stopped. Practitioners don’t like to wait until the end to summarize. They don’t like to expend effort thinking through things only to find out they were wrong in the first place. They are very active listeners. They’re going to stop you. Reframe conversation. Explore tangent ideas quickly. Pick things apart at a detail level. Because that’s how Do-ers operate. They don’t truly understand something until they take it apart and put it back together again.

But Do-ers hate being lied to more than anything else. Don’t know the answer? Admit it. Can’t think of the right number? Tell them you’ll get it. But don’t make something up on the spot. Odds are good that if a D-Suite person asks you a leading question, they have an idea of the answer. And if your response is outside their parameters they’re going to pin you to the wall about it. That’s not a comfortable place to get grilled for precious minutes.

4. Data, Data, Data

Once you’re finished, how should you proceed? Summarize? Thank you? Go on about your life? If you’re talking to the C-Suite that’s generally the answer. You boil everything down to a memorable set of bullet points and then follow up in a week to make sure they still have it. Execs have data points streamed into the brains on a daily basis. They don’t have time to do much more than remember a few talking points. Why do you think elevator pitches are honed to an art?

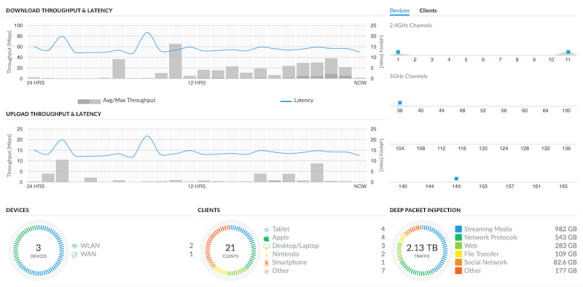

Do-ers in the D-Suite are a different animal. They want all the data. They want to see how you came to your conclusions. Send them your deck. Give them reference points. They may even ask who your competitors are. Share that info. Let them figure out how you came to the place where you are.

Remember how I said that Do-ers love to disassemble things? Well, they really understand everything when they’re allow to put them back together again. If they can come to your conclusion independently of you then they know where you’re coming from. Give them that opportunity.

Tom’s Take

I’ve spent a lot of time in my career both presenting and being presented to. And one thing remains the same: You have to know your audience. If I know I’m presenting to executives I file off the rough edges and help them make conclusions. If I know I’m talking to practitioners I know I need to go a little deeper. Leave time for questions. Let them understand the process, not the problem. That’s why I love Tech Field Day. Even before I went to work there I enjoyed being a delegate. Because I got to ask questions and get real answers instead of sales pitches. People there understood my need to examine things from the perspective of a Do-er. And as I’ve grown with Tech Field Day, I’ve tried to help others understand why this approach is so important. Because the C-Suite may make the decisions, but it’s up the D-Suite to make things happen.